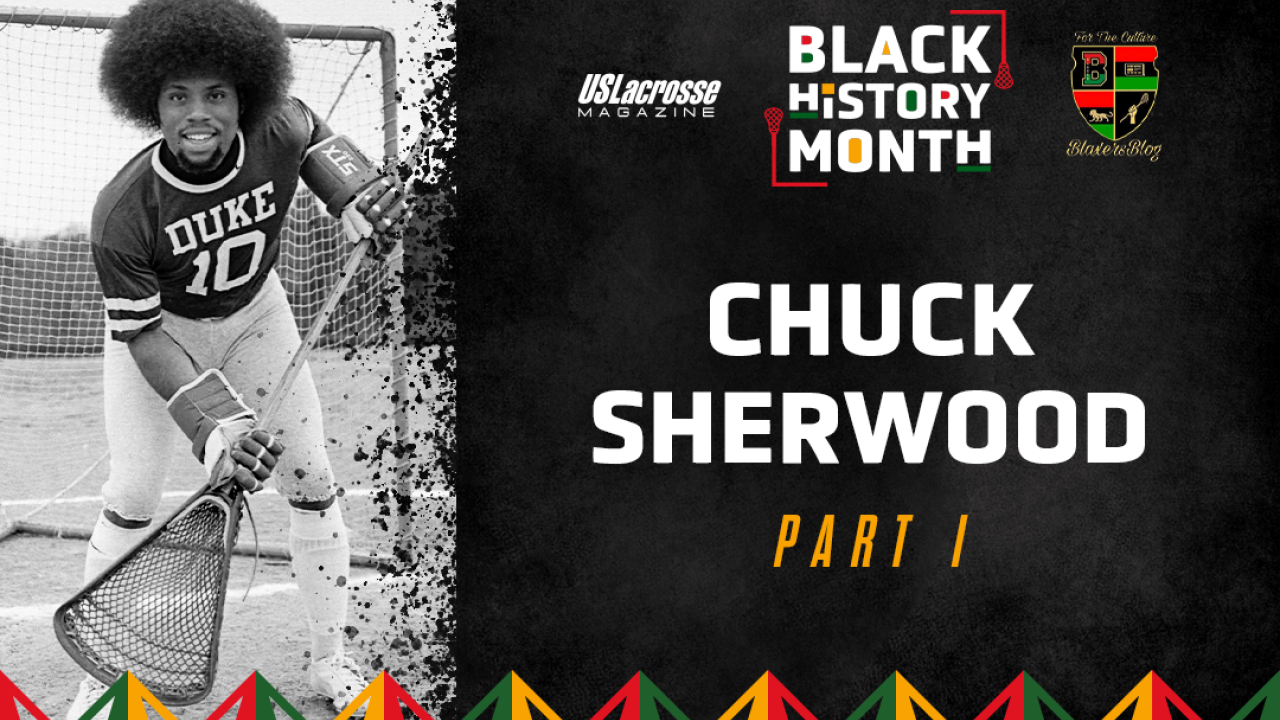

Blaxers Blog: The Chuck Sherwood Story, Part 1

What does it take to be a pioneer? Trials, sacrifice and sheer determination qualify as necessary traits. Your environment can help shaWhape you to adapt and react.

A barrier-breaking, record-setting goalie from Hempstead (N.Y.) knew what it took to uplift his community and family legacy forever. Charles “Chuck” Sherwood Jr. embraced new environments as the grandson of Jamaican immigrants and relocated from Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood at 8 years old.

Blaxers Blog and US Lacrosse Magazine are proud to share Part 1 of his story.

A few days before the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, Chuck Sherwood began his half-mile commute home from baseball practice at Hempstead High School and heard a crowd roaring from the football field. Sherwood was accustomed to playing in 30-degree weather as a youth baseball player, but this balmy, 50-degree day felt special.

As Sherwood edged closer to investigate, the vocals of a James Brown song blared from the speakers. Sherwood stumbled upon a full-on battle between what he called armor-clad gladiators jousting over a small rubber ball. He was enticed by the fluid passing and zipping sound that emitted from the players’ shots.

From Sherwood’s vantage point, the lacrosse action operated in a funky cadence that aligned with the song's instrumental. After the Hempstead crowd’s cheers intensified after a goal, Sherwood felt a fire ignite inside him.

Sherwood’s father, Charles, was a professional banker and Army veteran who played baseball in the service. Charles nearly relocated to Indiana to support the patriarch’s dream of playing Negro League Baseball with the Indianapolis Clowns. The only child grew up wanting to follow in his father’s baseball footsteps until he experienced this divine encounter that changed his life forever.

“Screw baseball, I want to play me some lacrosse,” Sherwood said.

Sherwood abandoned his centerfield position on Hempstead’s junior varsity baseball team and joined the JV lacrosse program. At the time, there were no tryouts. A few neighborhood friends doubled as Sherwood’s new lacrosse teammates, helping him feel comfortable in this new venture.

His friend, Gordon Thomas, was the only goalie and desperately needed backup. Sherwood was more than willing to learn the position and assist Thomas when necessary, starting a few games in the cage as a freshman. He still needed extra time to improve his performance, though.

In the summer, Sherwood joined the local squad in the Hempstead summer league sponsored by town of Hempstead and Nassau County Police. The recreational league showcased numerous talents, including a young John Danowski, now the Duke and U.S. men’s national team head coach.

Sherwood performed well in the summer circuit en route to winning the position battle outright over Thomas his sophomore year. Stopping bounce shots was a key factor in his promotion.

Hand-eye coordination played a key role in Sherwood’s transition to lacrosse due to the ground ball drills he routinely practiced as a centerfielder.

“Vision is important in becoming a good goalie,” Sherwood said.

Thomas subsequently quit lacrosse to rejoin Hempstead’s varsity baseball team. Years later, Sherwood made an admission to Thomas regarding their position battles.

“Man, if I didn’t compete against you, I might’ve never achieved in college,” Sherwood told him. “You taught me how to compete.”

Later in the 1969 season, Sherwood subbed into a game when his team was losing. He helped spark the Tigers, and the game finished in a tie. Sherwood’s clutch play earned the respect of Hempstead’s coaching staff as he became a varsity mainstay.

Sherwood’s best moment came during his junior year in a matchup against Carey High School. He made 28 saves in a game that lasted four overtimes. A referee notified Sherwood that the 5-4 victory was one of the longest known high school lacrosse game in history.

His Hempstead teammates ran across the field to dogpile Sherwood in a celebratory frenzy when the final goal was scored.

“Chuck had great toughness,” Danowski said. “He was a big man who filled up the cage and had great anticipation. He was very hard to score against. Nothing got through. As a goalie, you need that personality to not let the next shot get past you.”

This spring marks 50 years since Hempstead High School’s first-round loss to Danowski’s East Meadow team. The loss, Sherwood said, was influenced by the absence of Charley Hayes, Hempstead’s star defender who was taking a mandatory physical to join the military. That game in 1971 ended Sherwood’s high school career and marked his first encounter with Danowski.

In 1978, Sherwood accepted Danowski’s invitation and joined East Meadow’s summer team.

“When Chuck was in the goal, there wasn’t anything he thought he couldn’t stop,” Danowski said.

Danowski, of course, went on to tally 120 assists at Rutgers before making coaching stops at C.W. Post and Hofstra before becoming the head coach at Duke, Sherwood’s alma mater, in 2006. Devon Sherwood followed in his father’s footsteps at Duke as a walk-on goalie during Danowski’s first season.

THE ROAD TO DURHAM

Chuck Sherwood accompanied his teammates and Hempstead coach Hank Lunde to a roaring Nassau County semifinal right down the road at Hofstra University. Lunde spotted Duke head coach Bruce Corrie in the stands and introduced him to his Hempstead players. Corrie graduated from Hempstead in the early 1950s, before the boys’ lacrosse program was established in 1957.

It was 1970, and Sherwood was a junior without a place to continue his lacrosse and academic careers after high school.

Three years earlier, in 1967, the first Hempstead players under Lunde’s leadership went to college. Sherwood witnessed this historic milestone as an eighth grader.

Dean Rollins was bestowed All-Ivy honors at Brown and played in the 1971 USILA North-South All-Star Game. Michael Bigby was a Princeton alum who later became a physician in New England. Henry Williams played at Cornell and now serves as Nassau Community College’s director of financial aid.

John Sheffield, who graduated from Phillips Andover (Ma.), went to Penn and was another mentor for Sherwood. Sheffield was a year older and lobbied for him to join the Quakers during a recruiting trip with a few Hempstead teammates.

“If these guys could come out of Hempstead and get Ivy League degrees, I could, too,” Sherwood thought.

During Sherwood’s junior campaign, Lunde analyzed his star goalie as a “B” student while contacting prospective colleges on Sherwood’s behalf. Lunde explained to Sherwood that if he steadied his academics, Ivy League programs would accept him as a student. Brown and Penn pursued Sherwood heavily in the process.

Penn appealed to Sherwood due to its city locale in Philadelphia and his father’s wish for him to become an accountant. Sherwood’s father supported his idea of attending the school based on the Wharton School of Business’ track record. Penn’s head coach, James “Ace” Adams, attempted to expedite Sherwood’s admittance into the business school, but Penn rejected him.

Sherwood said he made a grave mistake when he informed Brown’s head coach Cliff Stevenson of his desire to attend Penn. Subsequently, Adams and Stevenson had a conversation about the situation, resulting in Sherwood losing both offers.

Sherwood also applied to Yale but was rejected.

After meeting Corrie at Hofstra, the Duke coach informed Sherwood that he would arrange a summer interview with him, a requirement for prospective players. In July 1970, Sherwood’s parents took him to Durham, N.C., to get the process started.

Awestruck by the famous Duke University Chapel and building aesthetics, Sherwood felt like he belonged on the scenic campus.

“Duke felt like a city of its own inside of Durham,” Sherwood said.

Corrie gave Sherwood’s father a tour of Duke’s campus and athletic facilities, and he was blown away by the lush greenery and architecture. At the time, Duke barely had 100 Black scholars matriculated.

In the months ahead, Duke’s warm winter climate, academic prestige and campus aesthetics were factors that solidified Sherwood’s decision to attend after exchanging monthly recruiting letters and calls with Corrie.

Forty-eight Black freshmen were enrolled at Duke in 1971, the most in school history at the time. Duke’s overall Black population involved roughly 125 undergraduates. Even though Sherwood would be entering an environment far different than Hempstead, where he played on a predominantly Black lacrosse team at a predominantly Black high school, Sherwood faced this new challenge head on.

After Sherwood’s acceptance to Duke, the university granted him a $1,500 financial aid package, and his father took out a loan to pay the remainder. Wittenberg, a Division III school in Ohio, was a finalist for Sherwood after offering him a full scholarship. Despite the overwhelming offer, Sherwood informed Wittenberg’s staff that Duke was his final choice.

SETTING RECORDS, BLAZING TRAILS

Bruce Corrie’s commitment to competition encouraged freshmen to compete on a level playing field with the incumbent starters. In 1971, Sherwood was in a battle with starting goalie John Hill.

Sherwood was arrogant, thinking he could beat anyone and everyone for the leading role. Hill instead remained the starter. Sherwood was named the backup.

“I had to work to get what I got at Duke, and in the long run, it was worth it,” Sherwood said, reminiscing about his freshman season during which he earned two starting opportunities.

But he wasn’t sure of his Duke future after receiving limited playing time.

During the 1972 winter break, Sherwood traveled to Morgan State to visit his childhood friend, Dave Raymond. Raymond would later be a two-time USILA All-American (1974-75) who would play in the 1975 North-South Game. Sherwood contemplated transferring out of Duke to become the starter for the Ten Bears.

Morgan State coach Howard “Chip” Silverman gave Sherwood a campus tour that led to a conversation. Silverman learned of Sherwood through his high school coaches and recommended that the sophomore finish with his Duke degree. Silverman left his card just in case.

Leading up to his Sherwood’s sophomore campaign in 1972, Hill earned a football scholarship and never returned to the lacrosse team. Seeing a path to the top spot on the depth chart, Sherwood came back with a vengeance to beat out Joe Bergin and become Duke’s starting goalie.

One of his best performances came in a shortened appearance. Against host Virginia, which eventually won the national championship, Sherwood made 20 saves before being replaced facing a 13-2 deficit.

Virginia went on to win 29-2, the worst loss in program history. Although Duke was beaten handily, this was a sign that Sherwood could make plays against top competition.

The positional battle in the cage was rekindled in 1773 when Hill decided on to make a brief return to lacrosse. It lasted three weeks.

Sherwood had a 30-save game against Virginia. Sherwood later made 18 saves against Washington & Lee, and Hill subbed in the second half in a 26-7 loss.

Sherwood didn’t start every game. Duke finished 7-8, and Sherwood was disappointed that he couldn’t hold onto the job. Sherwood came back hungry in 1974.

The junior put together a dynamite performance against Virginia for the third year in a row, as he made 27 saves within three quarters. When Sherwood was replaced by Bergin, over 3,000 fans — mostly Virginia faithful — gave him a standing ovation for his efforts. Unfortunately, Virginia’s offense was too tough to contain, and Duke lost 15-6.

“That was a game I wish my coach didn’t take me out early,” Sherwood said.

Later that season, Sherwood’s 28-save performance helped Duke upset Washington College in a 12-11 nail biter. But five days later, Duke lost 17-15 to North Carolina, the result of a late comeback falling short. Looking back, Sherwood said his team would have made the NCAA tournament with a win that day.

Instead, Duke ended the season 8-6 and earned a No. 18 ranking in the final national polls.

Leading into Sherwood’s senior season, Duke graduated a wave of talent. Recruiting efforts were lackluster.

Halfway through his senior season, Sherwood sensed an unexpected energy flow through his body. His parents urged him to travel back home after his upcoming contests against Drexel and the University of Baltimore.

The next available flight back from Durham was two days after the Baltimore matchup. Unfortunately, Sherwood had no idea that his 13-year-old sister, Lisa Anne, was struggling with a heart condition. She was diagnosed with Down syndrome as a child, and Sherwood cherished his relationship with her.

Sherwood suited up for the April 26 contest against Drexel. The Durham skies were overcast, and there was a cool breeze blowing. He held an advantage in the goal because there was no glare from the sun.

Despite what was going on at home, he put forth a 37-save performance in a 13-9 loss, setting a Division I record for saves in a single game. It’s since been surpassed by three other goalies — Ken Wessels (38), Ryan McQuade (38) and Mike Gillis (50).

“It seemed like every time I attempted to block or catch, I made a save,” Sherwood said. “The ball seemed like a volleyball that day. It was easy to catch.”

Three days later, Duke lost 18-8 to Baltimore. Sherwood then flew back home. It was Good Friday when Sherwood finally arrived in New York. His parents somberly informed him of his sister’s passing.

“I always felt like there was some connection to my sister that allowed me to play that well,” he said.

Sherwood’s collegiate career ended as Duke finished the 1975 campaign with a 3-10 record. Although Duke didn’t have the talent to stick as a national power during his career, Sherwood still left his mark.

He graduated with 583 career saves, a Duke record at the time. He’s since been passed on the list by Danny Fowler (624) and Joe Kirmser (847). Sherwood said he enjoyed his experience representing Duke and making a name for himself.

“I always believed that lacrosse was a good sport for our young Black kids to pursue a college education with,” he said. “Once you make it there, you have to do what it takes to stay in school.”

Sherwood said that some Hempstead alumni fizzled in college because of cultural differences, adjustments and long distances from home. He was happy to be one of the examples of those who made it.

“Hempstead did a very good job in giving generations of men opportunities to excel in life and college due to lacrosse,” he said.

While he may not have realized it at the time, Sherwood’s legacy would long be remembered. He was not done making his mark in lacrosse.

CHUCK SHERWOOD

Hometown: Hempstead (N.Y.)

High School: Hempstead (1971)

College: Duke (1972-75)

Notable Accolades:

- One of the first Black players in ACC lacrosse history

- First Black player in Duke men’s lacrosse history

- Career-high 37 saves against Drexel in 1975 (a then-Division I record which now ranks third all-time)

Brian Simpkins

Related Articles