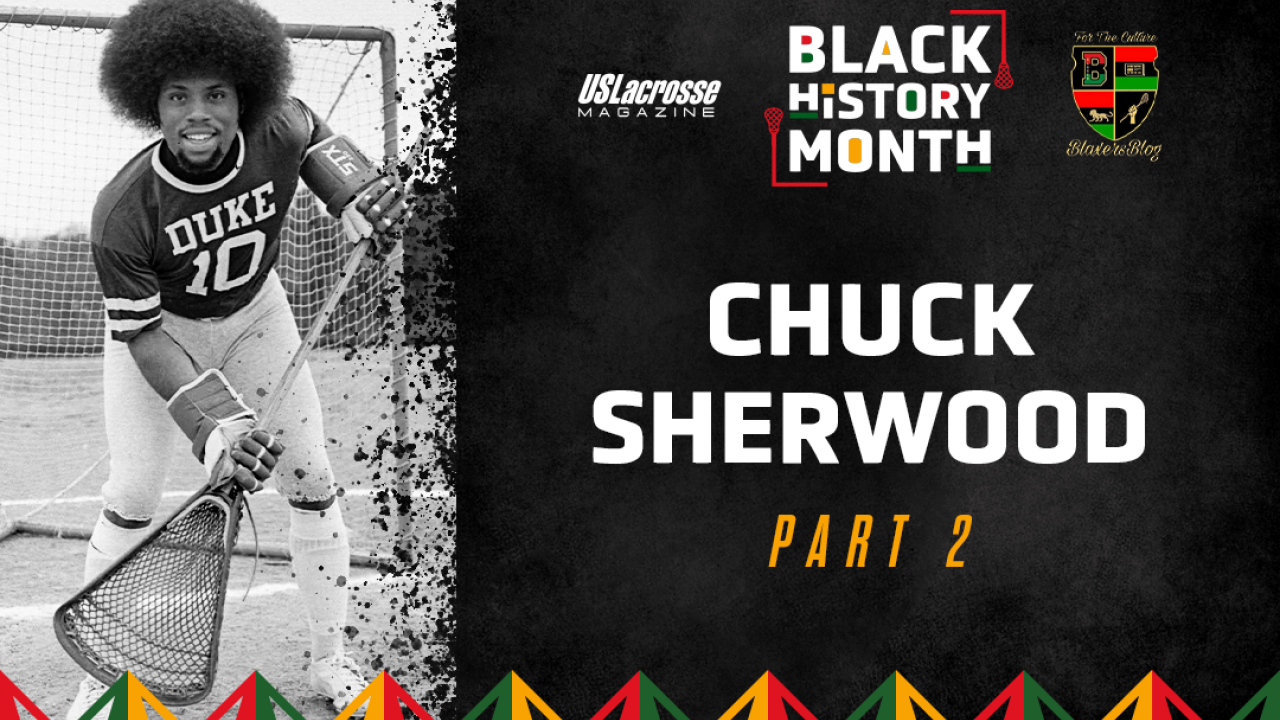

Blaxers Blog: The Chuck Sherwood Story, Part 2

What does it take to be a pioneer? Trials, sacrifice and sheer determination qualify as necessary traits. Your environment can help shape you to adapt and react.

A barrier-breaking, record-setting goalie from Hempstead (N.Y.) knew what it took to uplift his community and family legacy forever. Charles “Chuck” Sherwood Jr. embraced new environments as the grandson of Jamaican immigrants and relocated from Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood at 8 years old.

Did you miss Part 1? You can read it here.

Duke men’s lacrosse players see Chuck Sherwood every day. Even if they don’t realize it.

“The important thing is that every time I look at it [Sherwood’s plaque], I think of Chuck and his son [Devon],” Duke coach John Danowski said.

Located prominently in the corner of Duke’s locker room is a glass plaque that showcases the excellence of Chuck Sherwood, Devon Sherwood and a family endowment used to strengthen Duke’s men’s lacrosse team.

The left insert displays a 1975 photo Chuck Sherwood ready to make a save. At the time, he was 6 feet tall and 190 pounds. To the right is a picture of Devon Sherwood, Chuck’s youngest son, holding the 2010 NCAA championship trophy. In the middle is a family photo of Dawn, Chuck, Tre and Devon Sherwood.

In 2017, the Sherwood Family Operational Endowment was established to help Duke lacrosse players and other student-athletes. Each year, the Sherwoods deposit between $2,500 and $3,000 to the endowment, and the value will gradually amass up to $50,000.

The plaque serves as a visual reminder to Duke players of the standard of excellence set by the Sherwood family and reminds them of the confidence needed to overcome any forthcoming obstacles.

“I think [Sherwood’s plaque] represents something that happened a long time ago that wasn’t very celebrated,” Danowski said. “Chuck’s goal wasn’t to become a trailblazer. Duke was the best place for himself academically and to play at a high level. Men like that are people we really want to celebrate.”

All-American defenseman JT Giles-Harris said that plaque gives him a sense of pride.

“I feel proud seeing his plaque because he was the first to come through who looked like us and did what we do now,” Giles-Harris said. “There’s a sense of pride knowing he was the first one to take that step at our school for the sport.”

Carrying the torch Sherwood first lit feels “incredible,” Giles-Harris said. Some teams, Giles-Harris said, lack proper representation, whereas Duke showcases the diversity the sport can possess. Giles-Harris, Nakeie Montgomery, Tyler Carpenter and Cameron Henry are four student-athletes of color on the Duke team who cherish Sherwood’s impact.

“The ability to play lacrosse looking the way I do and representing where I’m from is pretty cool,” Giles-Harris said.

Montgomery is an electric senior midfielder who was integral in Duke’s run to the NCAA championship game in 2018. He’s a knowledgeable athlete who appreciates the history and those who came before him.

A music nut with a robust sneaker collection, Montgomery plays with a confident swagger that might not have been possible had Sherwood not stepped foot on Duke’s campus.

“Sherwood’s plaque is super powerful to me, and he’s a trailblazer for people who look like us that play the game,” Montgomery said. “His legacy is important, and we’re fortunate enough to follow in his footsteps.”

Giles-Harris, Montgomery, Henry and Carpenter are just the most recent players of color to leave their mark in Durham.

Devon Sherwood and Myles Jones were alums Montgomery studied before joining the program. Ironically, Devon Sherwood served as Jones’ host when he first visited Duke.

“Coach Danowski did a great job of pairing me with him because we’re both African American players and we’re both from Long Island,” Jones said. “We grew up in parallel situations where we were the only Black players on the team. It wasn’t like I could turn my head right or left and see players that looked like me, so it was easy for me to have a conversation about growing up and potentially being the only Black player on the team. He always told me about his Dad and what he went through.”

Danowski knows that lacrosse is a predominantly white sport. In order to better understand the Black players he serves, Danowski listens to their realities. Every player from every background has a story.

After the murder of George Floyd, Montgomery was outspoken in advocating for the Black community, helping to launch UNCUT Duke, a storytelling platform where he shared his experiences growing up as a Black youth in Texas.

It was met with universal praise, both for its honesty and for how Montgomery’s personality shined through.

“You couldn’t find two better representatives of the quintessential Duke man who leads academically, socially and responsibly,” Danowski said. “JT and Nakeie are great guys who uphold the spirit of Chuck Sherwood and are just scratching the surface on what they’ll become.”

HIS POST PLAYING DAYS

Sherwood was always a Duke man, even after his playing career ended.

In 1976, Bruce Corrie took a sabbatical and stepped down as the program’s head coach. As a result, the university hired John Epsey, who won a Division III national championship as a player at Cortland in 1973.

Sherwood had returned to Duke to be with his eventual wife, Dawn, who was working on her doctorate degree. They met while he was playing as an undergraduate and eventually married in April 1979.

While Sherwood was in Durham, Epsey approached him with an available assistant vacancy because the program needed goaltending expertise. With zero hesitation, Sherwood immediately accepted Epsey’s offer to rejoin the Blue Devils. Sherwood spent 1976 as Duke’s assistant coach, his first foray into a coaching field in which he would later leave his legacy back in Hempstead.

To make ends meet while Duke’s assistant, Sherwood sold his meal books for cash and bunked with his Duke buddies. The program endured a 5-7 season, and Sherwood returned back to Long Island. For the next 15 months, Sherwood supported himself while working at his uncle’s liquor store in Harlem.

In the summer of 1977, Sherwood decided to pursue graduate school in hopes of obtaining his master’s degree in sports administration. He said the only institutions offering that program were UMass, Ohio University and Grambling State.

Before making a final decision and heading off to school, Sherwood teamed up with Danowski on the 1977 Long Island Athletic Club team, which finished as a national championship finalist in June.

In the fall of 1977, Sherwood accepted Grambling State’s full assistantship offer. He worked evenings in the intramural sports department to fulfill the requirement and didn’t owe any money after graduation.

“Grambling was tough, and the courses were wonderful,” he said.

When Sherwood arrived at Grambling State, he encountered senior quarterback Doug Williams on his first day locating the sports information department.

Williams, a Black College Football Hall of Fame quarterback, ended his senior season as a fourth-place finalist for the Heisman Trophy that same fall. He later won a Super Bowl with Washington in 1988.

While at Grambling State, Sherwood met football coach and College Football Hall of Famer Eddie Robinson Sr., who holds the FCS (Division I-AA) record for all-time wins as a coach (408). When Sherwood finished his Grambling State coursework in eight months and was unsure of his future, Robinson Sr. was integral in influencing the next chapter of his life.

Robinson Sr. sent letters of recommendation and made calls to New York Jets president Jim Kensil on Sherwood’s behalf, landing him an internship within their player personnel department.

Once he arrived back home to Hempstead, Sherwood took extra graduate courses at Adelphi before beginning his internship with the Jets in September 1978.

The Jets were one of the first NFL franchises to utilize computer-aided systems for scouting and strategy purposes. Sherwood’s internship duties entailed research and inserting league wide player profiles into their database. After Sherwood’s internship ended, Jets director of pro personnel Jim Royer hired Sherwood as a full-time employee. Sherwood worked for the Jets for four months.

THE SHERWOOD LEGACY

Sherwood was on the verge of marriage after ending his tenure with the Jets, and he began coaching lacrosse back home in Hempstead.

From 1979-81, Sherwood balanced being an assistant varsity coach and head junior varsity coach at his alma mater with his part-time job as an academic counselor at nearby C.W. Post (now Long Island University). Sherwood switched careers in 1981, working for the Seagram’s Corporation on Long Island. The corporate grind made him miss coaching, though.

Sherwood sought to become a teacher. He was hired at an elementary school in Brooklyn, and upon receiving his certification in 1986, he was hired in Hempstead Public Schools as a teacher and head coach.

His predecessor, Alan Hodish, left coaching to pursue law, which led to Sherwood’s promotion as the boys’ lacrosse head coach in 1986.

“Hempstead needed an alumnus like me to work with our Black kids and help them through the avenues of education,” Sherwood said.

“Hodish had a dynamite team in 1983 who could’ve won a championship. That was one of the most competitive teams in Hempstead’s history.”

A young Clifford Smith Jr. (aka Method Man of Wu-Tang Clan fame) would play lacrosse for Sherwood in 1986. Method Man also played youth lacrosse under Hodish’s leadership. Method Man went onto partner with the Premier Lacrosse League to release a lacrosse anthem called “BOOM,” as well as an exclusive merchandise line.

Sherwood was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1988, prompting a sudden change of plans. When his vision was compromised, he stepped down as head coach and became the assistant coach in the middle school from 1989-92.

“Coaching at the middle school level was less stressful for me at the time,” Sherwood said.

Fred Opie surprisingly stepped in to replace Sherwood in 1989.

“I was very proud of him that he got the job because it was another Black coach with tremendous experience to take over the position,” Sherwood said.

Opie’s short stint ended in 1990, when he accepted a job at Gettysburg and served as the Bullets’ graduate assistant and defensive coordinator until 1992.

Hempstead fell into dismal conditions in the mid-1990s and hasn’t experienced a winning season since the 1980s.

Sherwood ended his coaching career altogether once his oldest son, Charles “Tre” Sherwood III, started playing high school basketball, football and lacrosse at nearby Baldwin High School. He dedicated his time to developing both of his sons’ lacrosse skills.

“He was always the benchmark for me,” Tre Sherwood said. “Growing up, I saw him be deeply ingrained in the community and an extension as other people’s fathers when many of his players lacked father figures.”

While in college, Tre played midfield for two NJCAA semifinalist squads at Nassau Community College in 2003-04. Following his JUCO career, he started at attack at Western Connecticut State University. During that time period, there were only a handful of Black attackmen in the country.

Tre Sherwood was impacted immensely by his father’s guidance. He continues his father’s mission of helping Black youth, having been a high school athletic director and coach in the Charlotte area. Tre Sherwood also serves as the co-founder and Director of PS8 Basketball.

Both of Chuck Sherwood’s sons took his messages to heart.

“As a kid, you want to be just like your father, and seeing his pictures helped me envision myself in the future before I took lacrosse seriously,” Devon Sherwood said.

Devon Sherwood followed in his father’s footsteps as a Duke goalie from 2006-10 while earning ACC Academic Honor Roll honors in 2010. He finished his collegiate career with a .555 save percentage and a 7.78 goals against average.

His father produced 583 saves and a .630 save percentage over 1655 minutes played.

Chuck and Devon Sherwood are the first Black father-son duo to play and graduate from Duke.

“A father and son who played at the same school is really special,” Danowski said. “The Sherwoods are very humble people and great role models for that next level of Black athletes who would consider Duke because of their legacy.”

A humble lacrosse pioneer, Sherwood is a storyteller. He details his life story as if he’s putting the listener in the moment. Years later, people will continue to tell his story to young Black lacrosse players looking to break into this great game.

“Funny thing is that I wasn’t aware of the barriers I broke when I played,” Sherwood said.

Those barriers he broke are certainly clear now as more Black players follow the trail he blazed.

“His legacy is important,” Montgomery said. “We’re fortunate enough to follow in his footsteps.”

Brian Simpkins

Related Articles