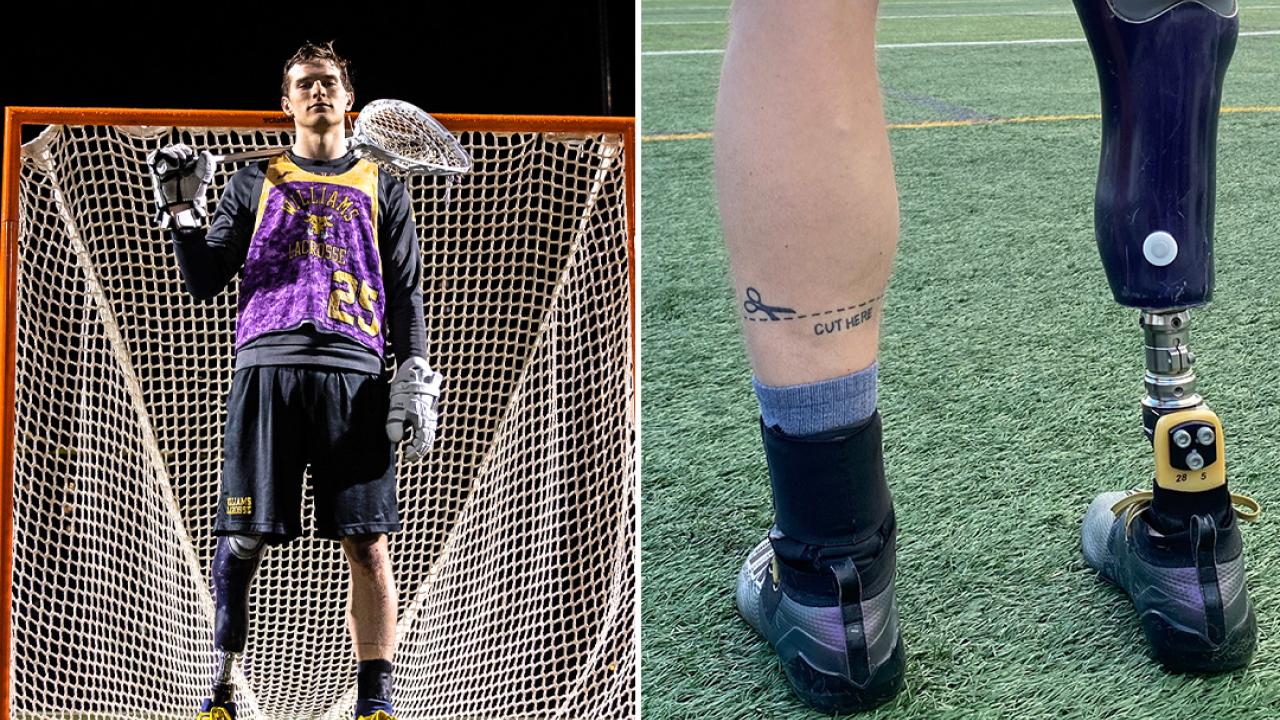

A Cut Above: Amputee Matt Freitas Stars in Goal for Williams College

Nunzio Blonde still remembers what the tattoo looked like.

A dashed line around the man’s left leg. A pair of scissors. The words “cut here.”

Definitely not a request Blonde had gotten before.

Matt Freitas made the phone call to Skin Deep tattoo shop on a whim in summer 2021. The shop doesn’t often offer same-day appointments, said the man on the other end of the line, but they could squeeze him in.

When Freitas explained the design he had in mind, the man seemed confused. But when Freitas walked in that afternoon, it all made sense.

The tattoo lines up with where doctors amputated Freitas’ right leg following a car accident on Jan. 4, 2013. By pure coincidence, Freitas had scheduled his appointment with Blonde, whose left leg had been amputated in 2019.

The experience, Freitas said, was “transformational.”

“For a lot of people, it's really difficult to ask questions,” Freitas said. “Because, I mean, you're walking down the street and you see somebody with a prosthetic leg. What are you going to do? Go say, ‘Hey, how'd you lose your leg?’ That's a scary thing to ask, even if a lot of people like myself are more than happy to answer. And so I got the tattoo as a way to give people that in.”

Losing his leg at age 11 could have been the end of Freitas’ lacrosse career. Instead, it pushed him to work harder — to go all in. He’s not only the starting goalie and senior captain at Williams College, but he also runs a lacrosse nonprofit called A Shot for Life, coaches at a summer camp for kids with limb differences and even competed on “American Ninja Warrior.”

“I maintain to this day that I don't think I would play college lacrosse if I hadn't lost my leg,” Freitas said. “Not that I didn't love the sport — I just frankly don't think I would have been good enough. Because I never would have had the work ethic to start lifting, start playing more competitively, try and make a club team, or try and compete against the best.”

TEN YEARS LATER, FREITAS still hates the sound of a car horn. It blared for what felt like forever after an oncoming car t-boned his dad’s car and ripped off the door that Freitas was napping against.

Just shy of his 12th birthday at the time, Freitas remembers every detail. His friend Zach sitting shotgun. The unimaginable pain. The EMTs trying to keep him from closing his eyes.

“The surgeon at the time decided right away: ‘If we don’t cut off his leg, he’s either going to die or he’s going to have a really poor quality of life,’” Freitas said. “I couldn’t be more grateful that he just decided in that moment ‘We’re not going to put him through that.’”

A few days later, Freitas was transferred to Boston Children’s Hospital, closer to his home in Weymouth, Massachusetts. Doctors fitted him for his first prosthetic, and they told him it would take 10-12 months for him to walk.

When Freitas initially awoke in the hospital bed, his first question wasn’t if he could ever play lacrosse again — but when it would be. His expected recovery timeline consisted of a few months before he got his prosthetic, followed by six months with a walker and another one or two months with a cane. Freitas didn’t want to wait that long.

The day he got his first prosthetic, Freitas shuffled into a Boy Scout event with his walker. But by the time his mom came to pick him up, Freitas was upright playing dodgeball, and the walker sat dejected in the corner of the gym.

He headed back to lacrosse practice less than a month later.

WHEN WILLIAMS HEAD COACH George McCormack met Freitas at a recruiting event, the goalie had sweatpants on. He had all the marks of a future college player: exceptional technical ability, leadership and communication skills.

It wasn’t until McCormack approached Freitas at the end of a game that he noticed Freitas’ prosthetic leg.

“He had obviously had to overcome some really great challenges,” McCormack said. “That actually made me more curious about him and want to recruit him more.”

Since the day of the accident, Freitas has known that he would have to work harder than most people. But he doesn’t want to be known as the guy with one leg, so he doesn’t mention it to his teammates much.

“I'm fortunate to have him in my program to set the example for others on how to deal with adversity,” McCormack said. “He doesn't bring it up. He doesn't make a big deal out of it. And he just does everything everybody else does. And he does it well.”

But sometimes that silence comes at a cost. If Freitas has a rough practice, he wonders if he’s just there as a charity case. When he gets blisters on his stump during running workouts and lags behind his teammates, he becomes frustrated and wishes he could just run faster.

“I'm definitely a suffer-in-silence and quiet type of guy,” Freitas said. “But every single time I'll hit a point where it's just like, ‘There's no point in me being mad about this anymore.’ Because my leg’s not growing back.”

For the most part, Freitas can do everything his teammates can. He has worked with strength coach Rob Livingstone to create modifications to weight room workouts when he needs them. A $25,000 grant from the Challenged Athletes Foundation allowed him to buy a new carbon fiber running blade that helps Freitas run faster for longer distances.

“I think I lost my leg because it gave me an opportunity to work harder than other people,” Freitas said. “The little positive aspects of losing my leg are the things I try to constantly remind myself of.”

Finding the self confidence that he has today, however, took intense trial and error over long periods of his life — and that struggle isn’t over. Freitas didn’t have many limb-different role models growing up. He can count on one hand how many limb-different players he has ever seen in college lacrosse.

Freitas doesn’t want younger athletes to have to fight the same fight. He spends part of each summer working at NubAbility, a summer camp in Illinois for limb-different athletes. It’s an opportunity for young athletes to learn from coaches who understand their challenges, possibly for the first time.

“For the kids it's awesome because you get to be with coaches who look like you,” Freitas said. “But for me, when I first started coaching there two years ago, it was the first time that I've ever been to a place where missing a body part was the norm.”

NEITHER FREITAS NOR BLONDE REMEMBERS exactly what they talked about during Freitas’ tattoo appointment in 2021. But both remember how it felt to be able to talk openly about the experiences and challenges that come with being amputees.

After hearing about the meaning behind Freitas’ design, Blonde was all in.

“Hell yeah,” Blonde said, gripping the needle in his hand. “Let's do this.”

OUT ON A LIMB

Think they can’t? Watch them.

Former Southeastern and Whitter men’s lacrosse players David DiPiazza and Miles Moscato and current Williams goalie Matt Freitas are leading the effort to establish a club team comprised entirely of limb-different athletes who will compete in tournaments this summer and fall.

The trio met as coaches with the NubAbility Athletics Foundation, an Illinois-based nonprofit that operates sports camps nationwide for congenital, traumatic and medical amputees. Among other limb-different athletes who have signed up to play are former Albany football player Eddie Delaney (all 6-foot-6, 250 pounds of the one-time two-sport standout), current Belmont Abbey attackman Quinn Smith, cancer survivor Sean Dever and Peleton-famous Logan Aldridge — a former lacrosse player who in recent years has become known as The World’s Strongest One-Armed Man.

— Matt DaSilva

Emma Healy

Categories

Related Articles