Trevor Tierney: A Tribute to Coach T, An Underdog Story

My father has an inauspicious jewelry box in his study at home. Dust gathers on the glass cover. Ten championship rings sit unworn, scattered unceremoniously inside.

They became relics — memories of special teams, people and experiences that went by too fast with the passage of time.

As someone who was raised by, played for and coached alongside Coach Bill Tierney, the following is how I remember his incredible coaching career as it comes to a close.

A tribute to my father, coach and childhood hero.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1984, my father drove me down to Baltimore in our family’s old rusted-out blue Volkswagen Beetle. He had accepted a position at Johns Hopkins as the eighth assistant for the lacrosse team (there was no NCAA limit on coaching staff size at the time) and as the head men’s soccer coach for about $15,000 per year with a wife and four kids at home.

Before we left, my grandfather (from my mother’s side) asked him when he was going to get a “real job.” My Uncle Tommy (my father’s brother) had to loan him a brown paper bag full of cash for a down payment on our first home in Bel Air, Maryland.

Despite the impracticality of it at the time, my father’s dream was to be a great coach and his passion was for the game of lacrosse. He had been raised in Levittown, New York. His father was a World War II vet and truck driver. His mother was a nurse. He inherited from them a tremendous sense of work ethic and toughness. With this humble, blue-collar upbringing, he fit the bill to play the underdog.

When he arrived at Hopkins, he tried to convince the other coaches of an idea that he had for a “sliding defense” rather than just trying to guard offensive players one-on-one all over the field. They basically laughed at him and told him to go warm up Larry Quinn (who would become one of the greatest goalies of all time) and go to class with Dave Pietramala (who would become one of the greatest defensemen and coaches of all time).

In the fall seasons, my father kept busy by driving the opposing soccer coaches insane as he ran lines of midfielders on and off the field to keep everyone fresh. He was the original Ted Lasso, coaching a soccer team despite not knowing most of the rules and conventions of the sport. His least favorite part of coaching soccer was the casual use of the word “unlucky.” In his mind, athletic teams made their own luck.

Despite his doubters in both sports, he brought home his first two rings, helping lead the Blue Jays to two NCAA Division I championships in lacrosse in 1985 and 1987. He also guided the soccer team to its first NCAA Division III playoff appearance in 1986.

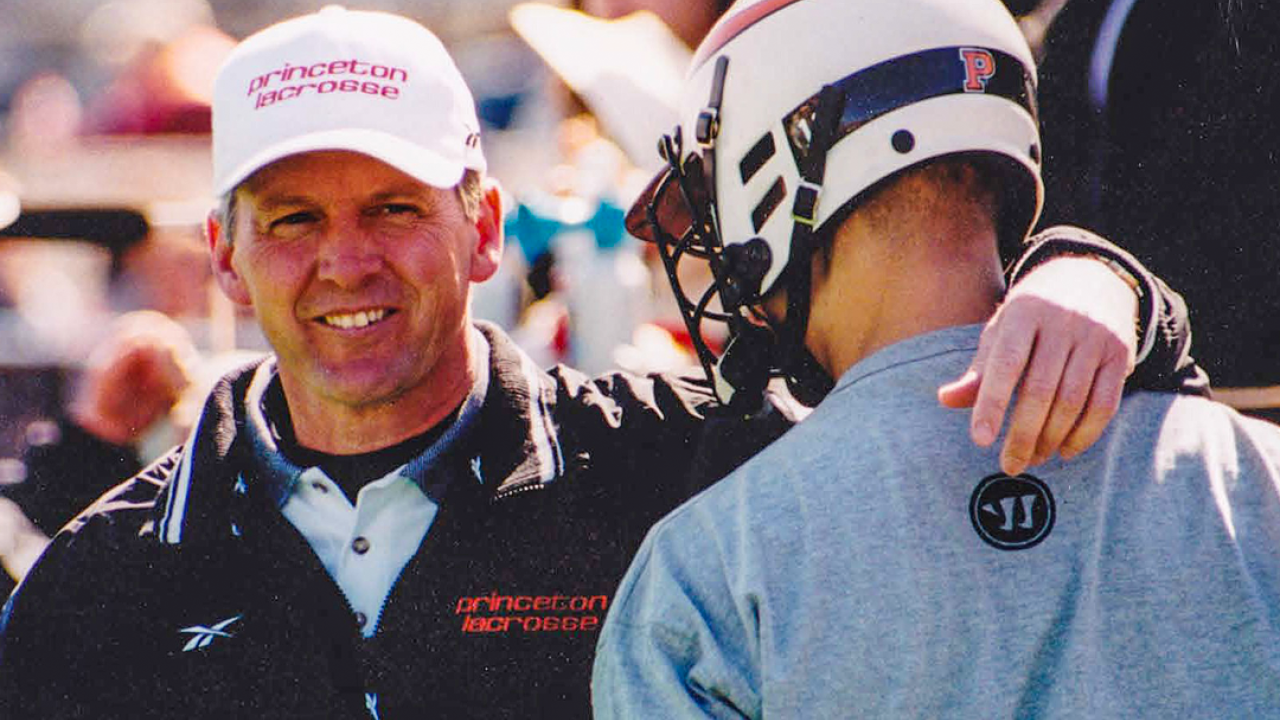

MY FATHER MOVED OUR FAMILY AGAIN — to New Jersey this time — so that he could take on his first Division I head coaching role. Princeton was considerably the worst team in the country at the time and could not win a game in the Ivy League, but he believed that he could lead the program to new heights. I went to his first team meeting in an old library in Dillon Gym, where he told the players they would compete for and win national championships.

It was a very rocky start, though, when the unwieldy Tigers went 2-13 in his first year. He came home after their last loss of the 1988 season on a rainy and cold night in Princeton and wondered aloud to our family if he had made a huge mistake.

It was not long, however, before Princeton managed its first major upset, beating Hopkins 9-8 at Homewood Field in the first round of the 1990 NCAA tournament. This was a drastic turnaround after a 20-8 drubbing by the Jays earlier that year, in which the Hopkins band played a mocking circus-like song after the 20th goal. My father never forgot that song. He used it as motivation never to lose like that again and as compassion never to score more than 19 goals on opposing teams as his Princeton program became dominant.

In the summer of 1990, Johns Hopkins athletic director Bob Scott — a legend of the game and in our entire family’s eyes — called my father to come back to Baltimore to be the Blue Jays’ head coach. He respectfully turned down the offer because he had promised his Princeton players and recruits that they would win a national championship before they graduated.

Sure enough, the Tigers found themselves competing in the final four on Memorial Day weekend in 1992. Princeton shocked the lacrosse world again on a dreary day in Philadelphia, beating national powerhouse Syracuse 10-9 in double overtime to win the NCAA championship. All-time greats like Scott Baciagalupo, Kevin Lowe and David Morrow — future Hall of Famers who believed in my father’s vision, system and culture — hoisted the walnut and bronze trophy in fulfillment of that promise.

AFTER THAT, OUR FAMILY VACATIONS CENTERED ON TRIPS TO FINAL FOURS on Memorial Day weekend. My father led his teams to 10 of them over the next 12 years, winning five more national championships (three of which were overtime wins) with the Tigers. Although he had cemented his reputation early on as a ball-control, defensive coach, the Princeton teams of the late ’90s — led by one of the greatest attack lines of all time with Jesse Hubbard, Jon Hess and Chris Massey — would average more than 15 goals per game and run the table for three championships in a row and add three more rings to his collection.

To top off this exceptional run, my father was asked to return to Homewood to coach the 1998 U.S. team for the ILF World Championships. The challenge with this team was the opposite of what he had faced in the past. Instead of endeavoring to get a group of players with lesser talent to believe in themselves and come together as a team, he was now tasked with getting the best players in the world to believe that it was actually important to come together as a team.

This mentality would prove to be critical in one of the greatest lacrosse games in history, when Canada came back from being down 10 goals to force overtime in the world championship. Rather than crumble under pressure, the U.S. team did what all Tierney-led teams did — they came back to their foundation and played with more discipline to win it in overtime.

A few years later, our annual family trip to the final four in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 2001 became an especially sweet memory when my father, my brother Brendan and I lived out our dream of winning an NCAA title together with all our Princeton brothers. Remarkably, it was another 10-9 OT win against Syracuse, just like the one Brendan and I had witnessed as ballboys on the field a decade earlier. That would be the sixth and final ring my father brought home with the “P” on it.

SEVERAL YEARS LATER, MY FATHER SHOCKED THE LACROSSE WORLD yet again announcing he was leaving Princeton and heading to the University of Denver to coach the Pioneers. He had accepted the opportunity for an interview with DU thinking that it would be a fun excuse to come out and visit me in Denver, where I had already lived for several years. When he returned to my condo after his day at DU meeting with the athletic director, the board of directors and the alums, the look on his face told me he was prepared to make one of the most excruciating decisions of his life.

It was time for a new challenge and a chance to become the underdog yet again. After my father accepted the position at DU in July 2009, many people in the lacrosse world said he could never win out in the Rocky Mountains, forgetting how implausible it had been for him to win at a small Ivy League school in the middle of Jersey.

And when the Pioneers lost to Syracuse and Jacksonville in the same weekend to start the 2010 season, he turned to me on the sideline (as his assistant coach this time) and again wondered aloud if this had all been a big mistake.

But over the next decade, he led Denver to five final fours and brought the NCAA championship trophy west of the Mississippi for the first time in the game’s history in 2015. As of this writing, that “DU” engraved ring may be the last one that he would bring home. He did this by getting his players to believe in the same vision, system and culture that had made his Princeton teams great over all those years.

You have to understand that for my father, it never had anything to do with bringing home championship rings for himself. Wearing a ring would mean that he was no longer an underdog, breeding complacency and entitlement. The aspect of coaching that my father loved was the process and journey of endeavoring to win the next one for the group of players that he coached at the time. Getting that team to believe in an impossible goal and then instilling the preparation and discipline to make that goal a reality — that was always the main thing for my father. His passion for coaching was in teaching his players to believe in themselves and each other, like he had done so for himself so long ago.

Over the past 40 years, Coach T filled the lives of hundreds of college student-athletes with amazing memories and lifelong lessons in a sport that we all love. Even more importantly, his teams brought so many incredible people together. Coaches, players, parents, administrator and support staff — all of us became connected as friends, family and community as we followed my father in his love for lacrosse and the dream he never gave up on.

Trevor Tierney

Related Articles